Before the Waves

Why would a young woman choose to serve in the military — and specifically the Navy — during World War II instead of other options, such as working in a plant as ‘Rosie the Riveter’ or planting a victory garden? This exhibit will outline the changing character of women’s work in the United States to see the challenges, and successes, women had in the years leading up to World War II.

Before the waves

Pre-20th Century Women’s Work

The issue of what historically has been considered ‘proper’ work for women is complicated. Far from one normal life trajectory, a woman’s role was often dependent on such things as social class, race, family economics and geographic location.

“Proper” Work

According to historian Robert Wiebe, in nineteenth century pre-industrialized America, women had a specific “sphere of competence,” caring for the home, which was the center of both individual and community life. Women helped to regulate a community’s moral character and identity, he contends.

As Alice Kessler Harris observes:

Women’s assigned work was equally a calling with men’s. As carpenters and masons were respected, so was the goodwife … (However) it would be a mistake…not to acknowledge that domestic work fell low on any hierarchical scale.

“Traditional Roles”

Women weren’t limited to “traditional” home-based work. Women also struggled for recognition in artisan trade organizations after the Revolutionary War, were considered part of the production unit in textile-based trades like weaving in eighteenth century England, and worked in nineteenth century New England textile mills.

But as the United State industrialized, community values shifted. Historian Robert Wiebe says the home became devalued, and work became the social and moral focus of workers.

Obsolete

The home-based work that women did was not just devalued, it was also increasingly being rendered obsolete. By the 1800s, mechanization meant that weaving and other crafts done inside the home were now less efficient and more expensive than factory fabric mills.

Alice Kessler Harris notes:

In the first two decades of the nineteenth century, wage work drew a sharp line between affluent women, who could afford to practice household arts without pay until marriage, and women, married or single, who needed to support themselves or help their families in the period of young adulthood before they set up their own families. Those who needed an income could soften the division between themselves and the better off if they worked at relatively genteel jobs such as teaching and writing, or if they worked at home.

Keeping Women Home

By the late nineteenth century, economic historian Thorstein Veblen sharply criticized the “conspicuous consumption” of what he dubbed the new “leisure class,” a group which included women whose sole purpose was to look nice and shop. Other upper and middle class women of this era, discontent with both the leisure and employment options open to them, began working in charitable/social aid projects such as Hull House or lobbied for women’s suffrage.

This lifestyle was enabled by a group of working-class women, who held positions in both domestic employment (maids, housekeepers) as well as sales jobs in stores. Anna Clark traces how a “rhetoric of domesticity” emerged with women encouraged to care for their children. Far from “traditional,” the stay-at-home wife and mother is instead a relatively recent development as Western nations industrialized, with working class women eventually emulating the actions of the more affluent.

Before the waves

World War 1 & the 1920s

The early part of the twentieth century seemed a golden age of sorts for women: women finally won the right to suffrage, Margaret Sanger began the birth control movement, and an equal rights amendment was proposed by Alice Paul. But, of course, things were more complicated than that.

Suffragists

As Nancy F. Cott notes, though winning the right to vote helped the women’s cause, it wasn’t enough.

By the 1910s the nineteenth century woman’s movement had gained entry to, although no transformation of, many avenues of social, economic and political power from which women had felt excluded.

However, the access was only for some women, who were tokens but not representative of the whole population. Their concept of feminism included equal citizenship but also economic independence and rights in sexuality.

Gradually, women began moving into new and different types of work, aided by two factors: industrialization and World War I. By 1910, thirty-six percent of the workers in electrical manufacturing plants were women, a percentage which remained relatively steady through the Depression.

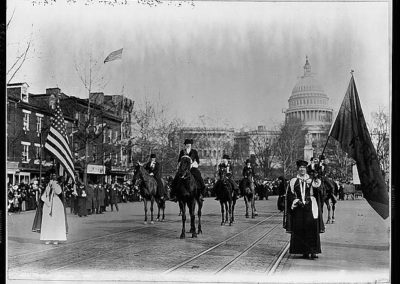

Yeomanettes

During World War I, Navy leaders found a loophole which enabled women to serve alongside men in jobs other than nursing. The women became known as “Yeomanettes.” Lorette Prevectus Walsh was the first to enlist in the U.S. Naval Reserve on March 21, 1917. Nearly 12,000 women served in all during World War I, due to a creative interpretaion of the Naval Act of 1916 by Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels. The Navy was already using women as civil service clerks. Daniels, a long supporter of suffragists, noted the Naval Act was vague, saying only that “all persons who may be capable of performing specific useful service for coastal defense” could serve in the Naval Reserve.

The women’s nickname (yeomanette) derived from how their classification of “Yeoman (F),” as in Yeoman (Female) sounded when spoken aloud. By the war’s end, the women were placed on inactive duty, and by 1925, the Senate closed the Yeoman (F) loophole, limiting reserve service to “male citizens of the United States.”

Roaring ’20s

As the 1920s began to roar, a new symbol of the independent woman emerged: the flapper, with bobbed hair and short skirts who, as Sheila Rowbotham notes, found:

New kinds of employment were opening up in banking, real estate, retail sales, administrative and clerical work…The number of ‘white collar’ women were growing. There was also an expansion in glamorous but unorganized jobs which were part of the growing leisure industry – everything from bowling alleys to the ultimate dream of the cinema.

Scholars are at odds as to just who these newly working women were. Alice Kessler-Harris contends work during wartime opened women to the possibility that marriage and work weren’t mutually exclusive. By contrast, Lois Scharf argues that women were only accepted as workers with the assumption that they would move back into the home after marriage.

Standard of Living

By the 1920s, maintaining a standard of living became difficult for less-affluent Americans due to a redefinition of “need.” Veblen’s notion of conspicuous consumption had migrated from the leisure class to working Americans. Technological innovations, such as the radio or the automobile, became family essentials. “Need” became defined not as basics such as food, clothing or shelter, but what a family was unwilling to go without. Critics said these women were merely working for “pin money” and portrayed them as selfish or frivolous.

Winifred Wandersee disagrees that these women were motivated by consumeristic reasons. She argues women with children and employed husbands worked because they were committed to family values. Work was a way for women to improve living conditions for their families.

Before the waves

The Great Depression

The Depression challenged the notion of financial independence and of the necessity of married women working. But it is also impossible to paint American experience during the 1930s with a broad brush.

Changing America

In the early part of the twentieth century, America experienced phenomenal growth due to an influx of immigrants. The country’s population doubled from the 1890s to the 1920s, with the bulk of the immigrants coming from “non-traditional” areas, such as Eastern or Southern Europe, who often settled in Northern cities. Meanwhile, a severe urban and rural technological divide emerged. Not only did Rural Americans lack modern conveniences, they also lacked the financial wherewithal of urban dwellers. Farmers’ economic troubles began far before October of 1929, actually starting with post-World War I surpluses, which sent food and grain prices plummeting. While industrial workers’ wages increased in the 1920s by twenty-five percent, farmer’s real wages had eroded during the same time period.

Government’s Role

The stock market crash of October 1929 may not have “caused” the Depression, but nonetheless it was a visible signal of the economic problems in American society. For at least half of the population, the Depression brought no great deprivation, though they were certainly aware of the hardships others faced. By 1932, unemployment had reached twenty percent, with a third of those who were working only working part-time. Families moved in together to save money and brought food to less fortunate relatives, strengthening “kinship ties.”

Lois Scharf says the government advocated the notion that women actually felt less strain due to the Depression than men, because no housewives lost their jobs in the crisis. This ignored exactly how unpaid work inside the home offered women any economic security. The government’s awkward bureaucratese is an example of the difficult negotiations during the era to determine exactly what service provides a “contribution” to society and should be protected by governmental assistance.

“Bad” Role Models

It wasn’t just the federal government who had difficulty determining if, or how, women were impacted by the Depression. Scholars disagree as to its exact impact on women; it either solidified their positions as workers, forced them out of the professional workforce and into less professional jobs, or re-awoke “antagonism to married women working.” As Lois Scharf notes:

The professional progress of women during the previous decades, even within this feminized field (teaching) came to a halt–a Depression decade legacy for women that continued beyond the 1930s. Married women especially faced scorn for working in these sorts of jobs and were viewed as ‘bad’ role models for children.

Women made up 24.3 percent of workers in 1930; the number rose to 25.1 percent of workers by 1940. In a period of economic uncertainty, Americans retreated from the social revolution of the 1920s. The encouraging trend that women could, and should, work in varied jobs, came to a halt.

Shut Out

Women often got little encouragement to pursue careers or professional jobs. For instance, the New York City Bar Association excluded women from its membership until 1937; from 1925 through 1945, United States medical schools placed a five percent quota on female applications. Young high school women were directed into less prestigious skills-based jobs, such as transcribing, billing and bookkeeping machinery operators. The jobs were assumed to be temporary and held only until a woman married.

Women didn’t necessarily chafe at these restrictions. As Winifred D. Wandersee notes:

The married women often felt herself in a far better social and economic position than her unmarried sister.

Before the waves

U.S. Propaganda

Webster’s Dictionary defines propaganda as “any organization or movement working for the propagation of particular ideas, doctrines, practices, etc.” It stems from the Latin congregatio de propaganda fide, or “congregation for propagation of the faith.”

The New Deal

Initially, the government took little direct action to assist those who lost their jobs, male or female. President Herbert Hoover’s plans included aid to farmers and encouraging businesses not to lower wages for workers. This was to little avail; by late 1932, thirty-eight states had no or virtually no banks open, with tightly limited withdrawals in those open in other states. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in 1933, he took drastic steps to move the country back to work and into economic recovery. His inaugural address (“the only thing we have to fear is fear itself”) and fireside chats demonstrated the new president was perhaps more adept at improving morale than actual living conditions for the average American.

Many of the programs that shaped the New Deals’ reputation were put into action during Roosevelt’s first one hundred days in office. A handful of women did find employment in the New Deal projects, like photographers Dorothea Lange and Marion Post Wolcott in the Farm Security Administration. The director of the project, Roy Stryker, says

We introduced Americans to America…The full effect of this team’s work was that it helped connect one generation’s image of itself with the reality of its own time in history.

New Deal projects like this laid the groundwork for the mobilization of World War II in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Pearl Harbor

Americans learned of the developments in Europe and Asia through reporting in America’s media: newspapers, newsreels and radio. In Europe, Germany was seeking domination through a series of successful invasions (Poland, Belgium, France, etc.) as well as extermination of “undesirable” populations (Jews, ethnic minorities, homosexuals, and others) in what would become known as the Holocaust. Meanwhile, Japan was seeking domination in Asia and the Pacific, through a series of battles in China and Southeast Asia. Italy was the only European country to side with Germany and was itself seeking to expand its dominance, invading Ethiopia. These countries would be known as the Axis; their opponent the Allies.

The U.S. officially remained neutral in the early years of the war, while taking legislative steps to help the Allies, such as allowing nations to purchase goods on a “cash and carry” policy or increasing the size of the Navy.

The surprise military strike by the Japanese at the U.S. Naval base in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1942 moved the United States from an official policy of neutrality to a state of war. The U.S. declared war on Japan the following day; on December 11th, the remaining Germany and Italy declared war on the U.S.

It’s estimated 60 million people died in World War II.

Coordinated Message

On January 13, 1942, the US government established a new department: the Office of War Information. Jordan Braverman notes the agency’s mission was simple: to spread propaganda throughout the country, improving morale during World War II. Propaganda, it is important to note, is not by definition, negative. Ongoing government projects soon fell under the OWI umbrella. One example is the Farm Security Administration photography project, which shifted its focus from America’s small towns and rural farms to factory and munitions workers. The purpose, according to Braverman, was to

formulate and carry out information programming to increase an understanding of the war by using the press, radio and motion pictures.

In every aspect of the media, from books to newspapers to newsreels to films to radio programs to advertisements to books, the war was front and center. Some media messages were directed at men, such as those encouraging enlistment. But others targeted women, including messages to buy war bonds, plant victory gardens or enter into work in war industries or the military.

Before the waves

World War II

While Japan has been at war with China since 1937, historians mark the start of World War II with the invasion of Poland by Germany in September of 1939. The United States would not get officially involved in the war until December 7th, 1941 with the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese.

WWII Economy

Even before the attack on Pearl Harbor the war helped stimulate the economy. By mid-1941, the United States shook off the last vestiges of the Depression as the war in Europe spread. As U.S. military needs grew, however, it quickly became evident that a male-dominant workforce would not be sufficient. Initially, women who were already in the workforce took over these jobs, but gradually married women also began working. The war allowed women to enter into the job market without apology. Working as “Rosie the Riveter” was framed by the government in posters and other propaganda as a patriotic duty. Maureen Honey observes

War work became a vehicle for women to shoulder their civic and moral responsibilities as good citizens, rather than a way to become more dependent and powerful.

But she also cautions it would be simplistic to think that women only entered the workforce to somehow do right by their country. Women also saw wartime employment as giving them a chance to reenter a job force they may have been forced out of due to the Depression, or to enter the labor market for the first time

Working in Wartime

The labor shortage lessened businesses’ Depression-era resistance to hiring married women. Women, however, didn’t necessarily flock to traditionally-male jobs. Sherna Berger Gluck argues left to their own devices, most women would have avoided war-related businesses like shipyards or production plants in favor of clerical work, which was seen as both cleaner and more respectable. Nonetheless they did apply for and begin working in, factory jobs. Factories, meanwhile, didn’t rush to make things easier for their female workers. The plants were often staffed twenty-four hours a day, but offered little to assist working mothers, such as child care. The government attempted to make working non-traditional shifts easier by expanding federal child care programs.

In 1944 surveys, seventy-five to eighty percent of women working in wartime areas said they planned to remain in the labor force after the war ended. The government had a different idea. Women were to move back into the home at war’s end. Because the work was conceived of as only a temporary disruption of “traditional” female roles, Lois Scharf and others argue that World War II offered little in the way or real of substantial change for female workers. Others, like Gluck, believe the women’s wartime experiences may have helped set the stage for social change in subsequent generations.

Military Options

Five months after the United States entered World War II, the federal government approved women serving in the military during the emergency. This was unprecedented. Women who “officially” served were previously limited to medical roles. The Navy Yeomanttes in Word War I were never formally sanctioned.

The Army was the first branch to receive government approval, forming an auxiliary female corps in summer of 1942. A month later, the Navy welcomed women, as full, not auxiliary members. The Coast Guard and Marines soon followed suit.