Uniform Identity

Even before the first boot camp class, military brass in the Navy and Coast Guard were discussing the uniform the women would eventually wear. There were high expectations; it was commonly known, as many of the women comment, that the Navy man’s uniform was the “smartest” in the service. The uniform would, after all, become the public face of the WAVES and SPARs, communicating both the image and the identity of the female volunteers. It would also become the focal point of the Navy’s public relations campaigns, seen in posters, photographs and film. As a result, before analyzing those campaigns, it is first necessary to understand the powerful image presented by the uniform, and what the uniform meant to volunteers.

Uniform Identity

Design

Sociologist and economist Thorstein Veblen criticized the “conspicuous consumption” of the fashionable woman. However, fashion can also have positive benefits, offering a way to establish and confirm identity. Hillary Radner sees fashion as a form of authority, allowing a woman to “establish and maintain her position within the social hierarchy.” The Navy uniform is an example of this idea in action: the well-designed outfit gave WAVES and SPARs, regardless of economic background, a type of social power.

A famous designer designed them for us and they fit beautifully. And you felt so comfortable. It was probably the most expensive thing any of us had ever had. Well made. Beautiful material. And besides, it had two pockets just inside where you could put Kleenex and look better.

Mainbocher was a well-known dress designer at the time. And I knew I would never have designer clothes, so there was my opportunity. So when someone says, “Why did you join the Navy?” I say, “Well, number one, blue is my color.” [laughs] I don’t look that great in khaki or green. Olive green or whatever the color was. But I have blue eyes so that helped that. And it was a nice looking uniform.

Initial Design

WAVES director Mildred McAfee recalls having little to do initially with selecting the WAVE uniform design. The first uniform presented was a deep navy blue, with a bit of patriotic braiding on the shoulder:

A red, white and blue stripe…it looked just like a chorus girl, you know. And I was simply struck, and I said, “We cannot do it.”

The braid was changed to blue. McAfee also successfully argued that the women would be more comfortable wearing flesh tones, rather than black, stockings.

Appeal of Clothes

Elizabeth Hawes, a fashion designer and writer from the era, wrote,

It is not very difficult for a designer to understand the motives of wearing clothes for physical protection. The hard thing is to grasp how important it is to many people to get psychological protection from their clothes.

Part of that psychic protection would include the confidence that comes from looking good (or chic). Elegant clothing could, in essence, give the wearer the authority to act in a certain way. Hence, a seemingly insignificant design element like braided trim, for recruits could be the difference between a refined image or that of a “chorus girl.” McAfee, a former dean of a woman’s college, understood this function of clothing, much more than the men running the Navy.

The Designer

Couture designer Mainbocher created the WAVES and SPARs uniform. Mainbocher was born in Chicago, trained in the New York fashion industry, and served at editor of Paris Vogue. In 1929, Mainbocher opened his own fashion house. His atelier, just off of the Champs-Elysees in Paris, was the first opened by an American in the City of Lights.

Mainbocher brought an almost messianic view to fashion, saying

I don’t believe that dressmaking is an art but I do think that dresses are an important part of the art of living, just as important as food, surroundings, work and play.

His fashions drew a sophisticated, self-assured clientele. One client was Josephine Forrestal, a former American Vogue writer who married the Secretary of the Navy, James Forrestral. She made suggestions for the initial unform design. Some worked, and some weren’t very practical McAfee recalls the initial blouse design was “simply impossible to iron,” useful for a socialite with a personal maid, but not so for women expected to work and iron their own clothing. Nonetheless, the personal connection of a Navy wife gave the Navy women entree into the high fashion world.

Uniform Elegance

Each woman interviewed not only mentioned the uniform unprompted, but also was aware of its couture provenance. For WAVES and SPARs, the uniform helped project a “high class” and “refined” image. It’s an image that was internalized by the recruits. Margaret Anderson said they “thought that the WAVES were the elite branch of the service.” This message was conveyed through the couture-designed uniform.

It was put out by Mainbocher, which was the company that made all the designs for the movie stars. And I’m sure if you talk to very many military women who were in the Coast Guard or the WAVES, the one thing they remember about their uniform is it’s Mainbocher.

Jane Ashcraft Fisher, World War II Coast Guard SPAR

Uniform Identity

Status and Recruitment

It is important to remember that this group of women was venturing into new territory, entering the previously male arena of the military. Ruth Rubinstein observes that uniforms are traditional images of authority in clothing, with a connotation of power over other, non-uniform wearers.

When I was in Norman we used to go into Oklahoma City when we had liberty. We’d stay in a YMCA. And we’d have service women from the other branches were there. They had all their [laughs] old Army and military-issued underwear. We got to wear our own things. That really meant a lot to me.

There was a lady with a little boy. He was about, I don’t know, three or four years old. He was standing very close to us. He was standing quite close to me. And he just kept looking at us. Oh, his eyes were just so big. I’m standing there and all of a sudden he reached over and just touched me on the arm. Then he looked over at his mother and said, “I touched one!” (laughs). It was like we were Martians or something.

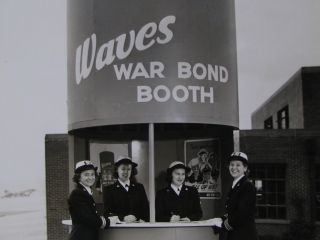

Recruitment & Publicity

The Navy used the uniform as a recruitment tool, pointing out the specifics of the design as well as its couture pedigree. One photo booklet, A Letter From Naval Reserve Midshipmen’s School (WR) Northampton, MA, was design to be mailed by a WAVE officer candidate to family and friends. While pictures of the WAVES in action (and, by extension, the uniform) are scattered throughout, five of the thirty-two pages in the booklet are devoted just to describing what the women wore. Mainbocher’s name is mentioned twice. The uniform, “of which we are so proud,” is described as “soft but trim” with “extremely glamorous lines.”

Personal Touches

The Navy learned from early mistakes by the Army. When the WAAC uniform was announced, newspaper writers focused as much on the Army-issued girdles as the uniform the recruits would wear.

By contrast, the WAVES didn’t discuss undergarments and attempted to present a dignified image. In a September 1942 radio interview, WAVES Public Relations officer Louise Wilde mentioned the “deep respect and pride” Navy women would feel about their uniform, but she also cautioned, “If I may make bold to speak for all my fellow officers, it’s the work to be done and not the material airs that count with them.” In other words, the work was far more important than a designer uniform.

White the Navy downplayed certain uniform elements (such as “unmentionables” like undergarments), the women interviewed did not. They talked of wearing brightly colored slips or fancy brassieres underneath their military uniform or of wearing shortie pajamas or fancy nightgowns to bed. This bit of individuality offered another “perk” of the uniform. Even though they might look the same on the outside, being a WAVE or SPAR afforded the women the opportunity to be unique underneath or in their own quarters.

Public Attention

The uniforms gathered attention. One recruiter described one of her job duties as walking around downtown areas in her uniform and simply talking to people who asked about it.

A darling girl came out in her WAVE uniform, a little blonde, cute as she could be. She was a recruiter. I think I made up my mind that minute that hat is the way to go.

– Mary Ada Cox Gage Dunham, World War II Navy WAVE

Uniform Identity

Group Identity

“The uniform, no matter how lowly, assures its audiences that the wearer has a job, one likely not to be merely temporary and one extorting a degree of respect for being associated with a successful enterprise. The uniform attaches one to success,” wrote cultural historian Paul Fussell. Unlike “Rosie the Riveter,” WAVES and SPARs wore a uniform, a visual marker that they belonged to something larger within the war effort.

I don’t know if the other services were as fussy, but we were tailor made. When I went into the Navy, at Hunter, they fitted us for our uniforms. And most of the people were more or less the same size. After all, we were all very young. But they made sure that the waist fit right and the shoulders and what have you. So we had – you know, when you got your uniform it fit you as it if were made to order. They were. We always looked nice.

They said we paid for our uniforms. But what they did, they gave us the money. And so that when we were measured and everything, we paid for it ourselves. We didn’t have to buy the uniforms, per se, but we had to take care of any alterations. We were given two hundred dollars. Some people really had to have a lot of alterations. I didn’t. So I came out ahead of the game!

Wearing the Uniform

Well-crafted and designed clothing can offer what fashion scholar Joanne Entwistle calls a “marker” of class identity. But equally important is how the individual “wears” the clothes and holds her body.

I looked at myself in the long mirror. By heavens, I did look impressive. The suit was beautifully cut, trim and efficient-looking without being stiff and masculine. It was the kind of tailored outfit I might have bought in civilian life–but in navy blue, with the fouled-anchor embroidery on the collar and black regulation buttons, it gave me the bearing of a woman in whom great responsibilities were vested. Unconsciously, I straightened and got a look of fire in my eyes.

– Joan Angel, Angel of the Navy: The Story of a WAVE

The Uniform Bond

The military gave the women a uniform, but could also take it away. Virginia Gillmore was called to assembly one morning with other WAVES. One young woman was marched to the front of the group. Her shiney brass button were cut off of her uniform jacket and she was escorted out of the assembly, and out of the Navy. Gillmore compared the event to combat training young men received and said it helped the remaining women to bond as a unit. For a WAVE, nothing could be worse than losing the uniform.

Best Dressed

Women outside the military initially attempted to copy the WAVE uniform design, even though they could be fined $300 and be sentenced to six months in jail if caught. In 1943, the WAVES (along with other women in uniform), were name as Vogue‘s “Best Dressed Women in the World Today.”

My WAVE uniform was the best piece of clothing I think I ever had because it felt so comfortable. The fabric itself was wonderful. Smooth. The color was great. And then it fit so well. I had never had something specially tailored to fit. In fact, they encouraged us to really be, take pride in our uniform, which we did. We kept everything really clean…They encouraged us, they told us where we could go have them specially tailored to have them fit. They wanted us to look very nice. I think we did. The clothes felt good on. They looked good on all of us. They were good designs.

– Virginia Gillmore, World War II Navy WAVE