Specialty Training

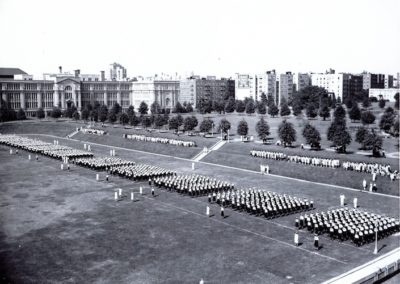

Boot camp lasted six weeks. Afterward, most women were assigned to an advanced training school, depending upon their abilities and the Navy’s needs. Like boot camp, first at Northern Iowa Teacher’s College in Cedar Falls and later at Hunter College in the Bronx, most of the training schools were established at colleges around the country.

Specialty Training

Getting the Job

Boot camp was initially designed as an orientation to Navy polices as in the first months of the WAVES women were only being accepted in three specific positions: yeomen, storekeepers, and radiomen. Things changed a bit by the time the Hunter College boot camp was established. A variety of jobs had opened up to women by this point – and it was up to the Hunter brass to determine which job was the best fit for each boot.

Placement Tests

Elizabeth Reynard’s creative skills were a huge asset when it came to helping the Hunter College recruits understand the different types of jobs available. She had dioramas of the various naval ships displayed at boot camp, and also brought in airplane and engine models as well as various equipment women might use on the job. She even set up a Naval History Museum on the Bronx campus.

But even though the women knew their options, and could request certain positions, their specialty training was often determined by a round of aptitude tests, which began even before the women enlisted. At Hunter, there were more tests, including a voice recorder and instruments to check a woman’s aptitude for control tower work. The Navy, frankly, wanted the most skilled women in each given position and the tests, when combined with Navy need, helped to determine who did what.

Complements

They told us about all of the jobs in the Navy for women, volunteer women, and the most coveted one was LINK trainer. Because you got to sit right next to handsome cadets and teach them how to use their their instruments in an airplane. And one girl even got to train Tyrone Power, a big heartthrob of the day. And so all of us wanted to be LINK trainers, that was always our first choice. But sometimes we didn’t have a choice. They had something called complements to be filled. And they would let the people at Hunter know what was needed and then the people at Hunter would just assign us. And sometimes they would listen to a request but mostly they would just fill out the complements for Florida or California or wherever we were needed.

– Virginia Gillmore World War II Navy WAVE

Don’t Get Your Hopes Up

When we were at Hunter College, we had to take tests. They took us around, and showed us all these different things that we could be put in for. I fell in love with control tower operator or Link trainer instructor, which was like a small plane on a pedestal. When the pilot is in there, it’s just like being in the cockpit and doing night flying stuff. They had patterns they had to fly and stuff like that. I thought it was fantastic. I thought it was the most interesting thing I had seen. They try to, they have interviews and they try to not get your hopes up. They said, “Well, you’ve never done any teaching.” . . . When she came in to give us our assignments, as she came into the room she looked at me. And she walked away, and she said, “Now, when I tell you what your assignment is, I don’t want to hear a peep out of you. There will be no screaming and yelling.” Afterwards, I realize she was talking to me, because she realized how much I wanted this job.

– Dot Forbes Enes, World War II Navy WAVE

Glamour Jobs

The Navy (and later Coast Guard) stressed that every job filled by women was important. But the rank and file didn’t necessarily agree with that assessment. The jobs which allowed women to break the “traditional” female mold were dubbed “glamourous.” These positions were generally based at Naval Air Stations: radio operators, control tower operations, pilot instructors, gunnery mates. Other jobs, which the women could do in non-military life (bookeeping or secretarial work) were seen as more mundane, and less desirable. Hospital work and parachute rigging were jobs that were considered glamourous or desirable by some and undesirable by others. Parachute rigging was rejected by some women because of an incorrect rumor that they would have to jump out of planes and test their chutes.

Many women told us they didn’t want one of the “glamour” jobs. They were happy to work as yeomen and storekeepers, content in their knowledge that they were “freeing a man to fight.” Others saw their more routine assignments as filling a need: they were assigned to a certain position because that’s what the Navy needed at that time.

Specialty Training

The First Specialty Schools

The Navy initially set up three schools for training. Storekeepers trained at Indiana University in Bloomington. Yeomen trained at Oklahoma A&M College in Stillwater (now Oklahoma State University). And radio operators, who would send and receive coded messages, trained at University of Wisconsin in Madison.

Combined Training

When the WAVES first enlisted classes began in Fall of 1942, women went through a combined training program, which included boot camp and specialty training for one of three positions: yeoman at Oklahoma A&M College, storekeeper at Indiana University Bloomington and radio operator at University of Wisconsin Madison. It took only a few weeks for the Navy to determine that this system wasn’t workable, and the three schools were transformed into speciality training facilities only.

Oklahoma A&M College

Oklahoma A&M College in Stillwater was selected as the first training facility for yeomen, the Naval term for secretaries. After the first few classes of combined boot camp and speciality training, Oklahoma A&M would revert to a specialty training facility for yeomen only. Women would spend six weeks after boot camp learning skills such as typing, filing and filling out forms “the Navy way.”

Indiana University, Bloomington

Indiana University in Bloomington was another of the first three training facilities. Storekeepers trained here. In Naval parlance, a storekeeper is a bookkeeper or accountant; their duties would range from office based bookkeeping duties to actually ordering various goods for the stores at Naval bases.

University of Wisconsin, Madison

The third training facility was set up at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where women were trained as “radiomen.” Their duties were to send and/or received coded messages via radio.

They had sailors there in training for radio, but to have this group of girls arrive — ooh! They put us in — oh, gosh, we had lush quarters. Barnard Hall. They put us in the University of Wisconsin campus. That’s where we trained. Radio. Morse code, morse code, morse code. And then a little bit more morse code (laughs).

– Helen Edgar Gilbert, World War II Navy WAVE

Specialty Training

Yeoman at Cedar Falls

When Hunter College opened as a boot camp in February of 1943, Iowa State Teacher’s College (now Northern Iowa University) was transformed into a training school for yeomen. The school would share training of yeomen with Oklahoma A&M College (now Oklahoma State University) in Stillwater.

We just got our orders to go different directions and mine was Cedar Falls, Iowa to yeoman’s school. I had gone to business college after high school, so that would have been on my application I’m sure as far as skill.

I had the best teacher in that school that I had ever had in any business classes I had ever taken. We lived in a dorm and we actually had the same mess hall as the girls, the female college students did.

Yeoman Training School #2

As the Navy’s needs for recruits increased (from an initial estimate of 10,000 to 80,000 by early 1943), it was evident that the WAVES would need an entire facility dedicated to boot camp training. Iowa State Teacher’s College in Cedar Falls was unable to fill that particular need and so the Navy turned to Hunter College in the Bronx, taking over the entire campus.

But the Navy and Iowa State Teacher’s College wanted to continue their relationship. So in February, 1943, Iowa State transitioned from a boot camp to the Navy’s second specialty school for yeomen, joining Oklahoma A&M in training what for the Navy was its most pressing need: clerical workers to support base operations across the United States.

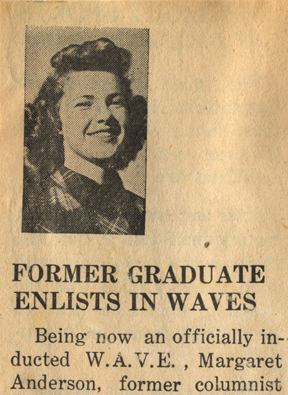

Same Company

WAVES Margaret Anderson Thorngate of California and Eileen Horner Blakely of Ohio ended up in the same training company at Cedar Falls. Both separately shared this same boot camp photo with the project as part of their oral history narratives They are in the bottom row; Horner is 3rd from the left and Anderson is 5th from the left.

Eileen Horner Blakely (left) and Margaret Anderson Thorngate (right) during Yeoman training at Cedar Falls.

Helping Out

WAVES who trained at Cedar Falls in the summer recall being asked to help the area farmers harvest the crops. The WAVES would get pay for their work, and it was completely voluntary. Some women were eager to try their hand at farm work (or do work which they knew from growing up). Others thought the work was too difficult and opted to not go.

Fun and Games

While the coursework was intense, the women also recalled time to be able to relax. The WAVES were able to use the recreation facilities at Iowa State Teacher’s College, which included a swimming pool and full gymnasium. Dances were often help as mixers between the WAVES, college girls and military men training in the area. And, of course, there were also seasonal pleasures, like building a snowman or getting into a snowball fight in the winter.

Specialty Training

Adding Key Schools

By Spring of 1943, Hunter College boot camp was in full swing. The Navy was matriculating roughly 2,000 women from boot camp every two weeks – and those women needed a place to train, especially in the key positions of yeomen, storekeepers and radio operators. Meanwhile, the SPARs was also producing women of its own, also in need of training. So the Navy developed relationships with additional colleges beyond the key quartet (Oklahoma A&M, Indiana University, University of Wisconsin Madison, and Iowa State Teacher’s College) to house Navy training facilities for the WAVES and SPARs.

Miami University (Ohio)

By late 1942, the Navy had determined that the University of Wisconsin wasn’t adequate for its training facilities for radiomen. So it expanded to another midwestern school: Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, where WAVES and SPARs learned Morse Code and the skills needed to send and receive coded messages by radio.

The campus had already been used as a training facility for men, so it was fairly easy for the Navy to integrate women into its training facilities. And many of the women who served there commented about how charming they found the small midwestern town where the campus was located – the town itself was only one square mile.

Training with Men

WAVE Janet Mead was one of those who went to Miami University for the Navy radiomen training school. She wrote home to her family about being on her first NDS5, a radio watch where the men and women trainees practiced sending and receiving messages to stations that were in the 9th Naval District: Great Lakes, Chicago, Milwaukee, Indianapolis and other midwestern bases. She bragged that the sailors weren’t as fast at sending messages as the WAVES.

More Storekeeper’s Schools

Just as the Navy discovered they needed an additional training school to keep up with the demand for yeomen, they too discovered that Indiana University wasn’t sufficient to train the numbers of storekeepers the Navy would need to staff bases stateside. So two more schools opened up: at Georgia State College for Women (now Georgia College and State University) in Milledgeville and at Burdett College (now closed) in Boston.

Specialty Training

Aviation Specialties

While much advanced training occurred on college campuses, other training, especially for the “glamour” jobs in Naval aviation, occurred at Naval Air Stations.

Link Instructor

Most women who were selected to learn how to run a Link trainer had some sort of experience as teachers. They would learn how to run the Link, an early flight simulation device. Link Instructors trained not at colleges, but at Naval Air Stations, often at the Atlanta NAS in Georgia.

It’s just a big box, but when the person gets in it you’re simulating something like instrument flight. The person operating it is outside and they have a little round device. It’s about a foot wide and it’s called a crab. The person in the link trainer is the pilot, it’s like the inside of the cockpit of the airplane.

– Jeanette Schaeffer Alpaugh, World War II Navy WAVE

Control Tower Operator

At Naval Air Stations, some women worked in the control tower, directing aircraft. It was known as a difficult and stressful job, but also was considered highly desirable.

One girl wanted to be an air control operator. And just wanted to be it so badly. Lovely girl, from the south. And they just sort of hesitated. Because they thought her southern accent might not be clear enough. But she was lucky and it was fine. They took her and she was so glad.

– Pat Pierpont Graves, World War II Navy WAVE

Machinist’s Mate

Machinist’s Mates also trained at Naval Air Stations. These were the women who would work on planes and other aircraft machinery, or who would help direct the planes on runways as they were landing. While Rosie the Riveter may have put some of the Navy planes together, it was the WAVES who kept the planes in working order.

I can remember one time at school, we were covering ailerons (the hinged part of a plane’s wing). At that time they were covered with fabric, not metal. (The training instructor) came back and he looked at me. He said, “You’ve done this before.” I said, “Yes, sir.” “Where?” I said, “Well, my uncle was only 11 years older than I and he was a pilot. He’s the one who taught me to fly.” He also had his own plane at an airport and we did everything on it, so I had an idea before I ever got in. But that’s what I wanted to do.

– Betty Bruns Lord, World War II Navy WAVE

Parachute Rigger

While Parachute Riggers didn’t have to jump out of a plane to test their chutes, they did have to watch as sailors tested the equipment they made at the end of training. The women had to be skilled seamstresses with a strong attention to detail. They trained at the Lakehurst Naval Air Station in New Jersey, the same place where the Hindenburg caught fire and was destroyed in 1937.

When I was in class, we had to pack a parachute…We had to pack it up so that it would work again. We did that, and laid it on the table. The instructor would come along and just pull the ripcord. Find out if it was going to work. He found one that didn’t work. He picked up a chair and threw it across the room. The girl who had packed the chute was in tears. It was a real lesson for us, because that chute wouldn’t open. She left a little stick–just a loop of the shroud line, so it never would have opened.

– Phyllis Jensen Ankeney, World War II Navy WAVE

Specialty Training

Other Specialties

Like those assigned jobs in Naval aviation, women assigned to the hospital corps and other speciality jobs trained at Naval Air Stations.

When I look back what intrigued me was the tests, the battery of tests that they gave us. I had a very nice gal who finally interviewed me. She made me feel good. Of course, she said with my bad eyesight I wasn’t eligible for control tower. The next billet that was was Link Trainer and they didn’t have any openings. So she put me in gunnery, aerial gunnery.

Pharmacist’s Mate

Any WAVE who worked for the Naval Bureau of Medicine and Surgery was known as a Pharmacist’s Mate. This was actually a catch-all classification of sorts: it included women who worked in an actual pharmacy as well as X-ray technicians, physical therapists, dental and optician’s assistants, and physician’s assistants or general hospital corps.

The women trained alongside men and the first groups received their training at one of 17 Naval Medical Centers scattered across the country. In December of 1943, that training was consolidated at two hospitals: the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, and Great Lakes Naval Air Station outside of Chicago

Gunner’s Mate

Like Link Instructors, WAVES who served as Gunner’s Mates were often former teachers. The job involved teaching men to shoot at moving targets, often from a moving location, such as a ship or plane. In training the women learned not only how to give instructions, but also how to operate the sometimes-cumbersome guns safely, often loaded with live ammunition.

We went through the same program that the men did. We shot machine guns, shot guns, pistols. We did the whole program as if we were going to be gunners. And then those who went on, sometimes to a more advance gunnery. We were the very, very beginning. How to aim was what it really was. That’s why we shot guns and machine guns. How to aim. And we were teaching how to aim at planes coming.

– Pat Connelly, World War II Navy WAVE

Aerographer

An Aerographer was the Navy classification for weather forecaster or meteorologist. Women would use a variety of tools to determine the forecast, including deploying weather balloons. Training was on the Naval Air Station in Lakehurst, New Jersey.

We had an intensive course in meteorology and forecasting and entering weather maps. You had to memorize all of these weather codes. You know, when you see a weather map it’s got the pressure and the temperature and the rainfall. And what kind of clouds there are and how much rain has fallen in the last six hours and all- and this all has to fit under a dime when you entered it. You entered it dipping a pen in India ink and entering this on a map.

– Liane Rose Galvin, World War II WAVE

Specialty Training

Reactions

“Military regimentation, such as the fish-out-of-water experience of boot camp, would cement (the women’s) new ties through social cohesion. In effect, the Navy would become a wartime family for the women, characterized by a shared military experience,” Kathleen M. Ryan wrote when speaking about this WAVES and SPARs archive. “Surviving” boot camp became a crucial component of the women’s shared identity.

Men’s Work

You could no longer mention the opening of another aviation rating without having hundreds of requests pour in … That was the glamour. And so many of them who wanted to get into aviation had been secretaries or something, so they didn’t want to be a yeoman. They wanted to do something different. They wanted to get their hands into something.

– Joy Bright Hancock, World War II Navy WAVE officer & World War I Navy Yeomanette

Being Places

I wish I knew [how I was selected for air traffic control tower school]. I often wondered. I finally came to the decision that I didn’t have so much accredited knowledge, but I must have- someone saw potential. That was it. Potential. With the interview that was conducted, we were interrupted, as soon as we were free to talk again, I initiated, I stated it. I was so enthused. The lieutenant who was in charge, the woman lieutenant said, “Why do you want to go and be a controller?” I said, “Because it’s so exciting!” I left afterwards and I thought, “Oh what a dumb thing to do.”

– Violet Strom Kloth, World War II Navy WAVE

Letters Home

Dearest Daddy . . . At night we can hear the front, see the trees lose their leaves, and smell bonfire smoke. The campus is beautiful and sprawling over a great space. I’m certainly going to like it here.

– Janet Muriel Mead,World War II WAVE, in a letter home to her family from the radiomen school at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio

“Best Training Ever”

No matter which specialty school, the women interviewed praised the quality of their training.

It was probably the best instruction I ever had. The most effective teaching. The reason they did it is we had to get up to 60 words per minute in doing shorthand. And it was entirely foreign. That meant those teachers had three months to get all of us so that we could do 60 words a minute in shorthand. And so they moved rapidly. We would, “But we’re not ready for anything new!” And they’d say, “Yes you are. Let’s go!” And they’d introduce new elements of the program and kept instructing us: “Don’t worry, don’t worry. It will come to you. It will come to you.”

– Virgina Gillmore, World War II Navy WAVE