The Media Campaign

The Office of War Information had a specific goal during the war years: a message about the war in every bit of media produced, be it by a government agency or an independent author or film producer. As a result, the Navy tightly controlled the outside image of the WAVES. No matter the media source, the message often followed a script which was developed and approved by the Navy publicity bureau.

The Media Campaign

Office of War Information

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government created the Office of War Information, with a goal of coordinating media messages during the war.

War Messages

The OWI began its work in January of 1942. The goal was to have a war message in every media output: from films to books to magazines to advertisements. The mass media was a willing participant. Sue Hart notes:

The identification of certain values as particularly American was a significant contribution…to home front morale and resolve. Role models of “real” or “true” Americans were created by advertisers, movie makers and songwriters–and the rank and file followed their lead cheerfully, for the most part.

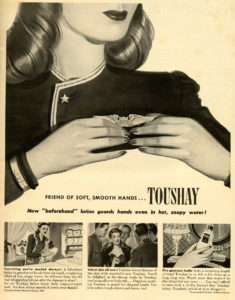

This ad for Toushay lotion appeared in Life magazine. It’s one example of how advertisers incorporated the military into even seemingly unrelated products. Note the military styling on the woman’s outfit in the large drawing, and how the Toushay user is surrounded by admiring servicemen in the middle small drawing.

A Messsage in Every Ad

Ads sometimes went to curious lengths to make sure the war message was there. A wide variety of products, from canned vegetables to deodorant, used ads with military or patriotic themes.

This ad for girdles shows a military woman (either an Army WAC or a woman’s Marine, based on the hat) behind the wheel of a jeep-like vehicle clad only in her Musingwear all-in-one support device.

Red Cross, Gold Cross

This shoe company took out a two-page ad in Life to promote their name change from “Red Cross” to “Gold Cross”; the switch was likely made so people wouldn’t confuse them with the International Red Cross, an aid organization.

In this case, the shoes are fashionable and functional for a host of war workers: Rosie the Riveter, nurses’ aides and even military women.

Chesterfield

This ad for Chesterfield cigarettes served triple duty. It promoted

- the product

- an upcoming film (Secret Command called by its working title in the ad)

- wartime service.

Actress Carole Landis is dressed in a military-type uniform (she’s just “back from the war zone”) and she’s surrounded by admiring soldiers. As a bonus, the ad reminds readers that “what your boy wants most (are) letters from home.”

The Media Campaign

Publicity Goals

The Navy, like other military branches, had its own Public Relations Division. It and the Office of War Information would need to work together to develop a consistent message about the WAVES.

The Navy’s Goals

Individual Naval Districts developed their own publicity plans during the first year of the WAVES. Most notable was District 3, which included the Hunter College boot camp. Boots filled out Public Relations Form A, which was used to promote stories to hometown newspapers and learn more about the boot’s interests.

In October of 1943, the Navy and OWI co-published the Information Program for the Women’s Reserve of the US Navy, which was distributed to reporters and media outlets nationwide. It not only suggested story topics and approaches, but also times for stepped up publication due to anticipated needs (November and December of 1943; and April, July and November of 1944)

Military Women as Cover Girls

Military women showed up on a wide variety of magazine covers. WAVE Leader Mildred McAfee was featured on a cover of the news magazine Time. Military women in various uniforms showed up on fashion publications Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue. Other magazines catering to specialty audiences, like the New Yorker or romance publications, similarly showcased women in the military.

Life covers show how women were used in military-themed covers. In the one superimposed over the video, a woman bids farewell to a soldier from a train station. She’s in civilian clothes and the man is in a uniform. In the cover directly above, a quasi-military woman is shown at work: she’s one of the women who would be part of the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots, or WASPs.

Military Women as Centerfolds

Military women were also portrayed as objects of desire. In Esquire, pin-up artist Antonio Vargas used the WAVES as inspiration in his annual calendar in 1944. The April woman portrayed is a WAVE-to-be. As she says in the poem which accompanies the drawing, “I’m going to join the Navy WAVES and help the war to halt, and also show my Navy beau that I am worth my ‘Salt!’”

The would-be WAVE was the only military woman featured in the calendar, but patriotism was still evident in the other 11 calendar girls: the poems talk of paying high taxes as a patriotic duty and features a woman dressed up as George Washington.

The Media Campaign

Magazines

Magazines were a major source of news and entertainment during the war years. The photo-based weeklies, such as Life and Look, were especially popular. Life averaged a circulation of two million people a week. These publications, and others, offered stories about military women.

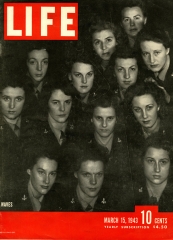

The WAVES Cover

The first magazine cover to feature the WAVES was an issue of Life, published in March of 1944. The cover was created before the Navy issued its publicity guide, but nonetheless, the women shown reflect its goals. Their somber expressions make appear to be serious and dedicated to the work at hand. Photographer Martin Muncacsi shot the women as a group, in uniform, rather than focusing on only one or two of the WAVES. They have natural hairstyles and little or no makeup, apearing to be average women who enlisted in the Navy, not cover-girls selected by the magazine because of their attractiveness or comely figures.

Articles

Inside the magazines, articles showed women at work, and occasionally, at play. This Life spread from April of 1943 shows WAVES looking at fashions that are “off-limits” for the duration of the war. Other articles show women bidding their former lives goodbye, or the various jobs that were open to military women.

In regards to articles about the WAVES, what’s interesting is how the magazine articles echoed not only the desired timing for publicity, but also the Navy’s desired goals. For instance, spreads in Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue featured WAVES at work at NAS Jacksonville. The photo essays appeared in November (Harper’s) and December (Vogue), dates identified by the Navy as times for increased publicity. The theme was the personal enrichment women could receive through Naval service, one of the secondary goals of the publicity guide.

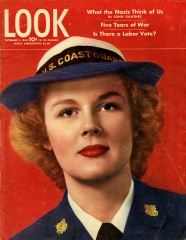

The SPARs Cover

In contrast to the WAVES, the SPARs didn’t have a similar internal coordination for their publicity. Instead, they relied more on the work of the OWI. This Look cover from September of 1944 features a SPAR on the cover. But unlike the group shot in Life WAVES cover, where the women wore little make-up and appeared serious and hard-working, the solo SPAR has perfectly coiffed hair and picture-perfect make-up. She is much more a traditional “cover girl” than the WAVES.

The Media Campaign

Books

Like the magazine industry or Madison Avenue, the book industry too embraced the role books could play in improving morale during wartime. They established a “Council of Books in Wartime” to help make the industry essential to the war effort and portray reading as a patriotic duty.

Journalistic Narrative

Each service branch would be represented in books during or immediately after the war. And several books focused on either WAVES or SPARs.

The dust jacket for The WAVES: the Story of the Girls in Blue says that author Nancy Wilson Ross interviewed “hundreds of girls” to discover just what it was like to be a WAVE. The 1943 book details the various qualifications and some experiences of Navy women, even going so far as to included a list of requirements and application guidelines, an aptitude test for enlistment (with answers), a list of frequently asked questions, and the pay scale for both officers and enlisted women.

This particular copy has a handwritten inscription inside the front cover where Gertrude tells her friend that she hopes the young woman will head to the Office of Naval Procurement and enlist in the WAVES.

Fictional Encounters

Helen Hunt Jacobs was already an established author with five books to her credit when she wrote “By Your Leave, Sir”: the Story of a WAVE. The 1943 book is a fictionalized account of the experiences of a WAVE in officer training at Smith College. Hunt Jacobs, an officer in the WAVES, created a thoughtful book with a conflicted heroine, an independent woman who wonders about the necessity of war even as she is joining the WAVES. The tone struck a chord with readers. “By Your Leave” was first published in July of 1943. By January of 1944 it was already in its fourth printing.

Other Fictions

While “By Your Leave” was written for an adult audience, other fictional books about the WAVES aimed at a younger demographic. Books were often part of a series aimed at teen readers.

In some cases, the books even use the same cover art. For instance, one series published one book that tells the story of a woman who wants to enlist in the women’s reserve during World War II – and a second (with the same cover art) portraying a romance about a woman who is the daughter of a lighthouse keeper. There is no reference to the Navy, WAVES or Coast Guard other than on the cover. It would appear the publisher was using the popularity of the women’s services in its cover art as a war to lure readers into a book.

Meanwhile, in Sally Scott of the WAVES, author Roy J. Snell depicts a young WAVE with a groundbreaking – and not regulation – short wave radio that helps save the day.

Memoir and Memory

World War II-era memoirs focused on the fun and adventure of joining the service. Joan Angel’s Angel of the Navy (1943) is told in a chatty, first-person style and includes cartoonish illustrations of the escapades she describes.

I could write a whole book about sleeping in an upper (bunk) … the ladders which had been ordered were still on their way. That made getting in and out of bed an gymnastic procedure somewhat related to mounting a bronco. One minor accident during our boot training occurred when a girl fell out of an upper berth. Possibly it had something to do with her system of somersaulting out instead of doing the “double-decker-swing.”

A similar tone is found in Three Years Behind the Mast by Mary C. Lynn and Kay Arthur. The book, published in 1946, looks back on women’s military service in the Coast Guard SPARs as a series of amusing “fish out of water”-type encounters between women and the regular military.

The Media Campaign

Movies

Hollywood was a willing participant in the government’s drive to incorporate a war message within films. While not every film was war-themed, a look at the Oscar winners and nominees during the war years demonstrates how pervasive the policy was: Mrs. Miniver (Oscar winner, 1942), Casablanca (Oscar winner, 1943), Since You Went Away (Oscar nominee, 1944), Anchors Aweigh (Oscar nominee, 1945), The Best Years of Our Lives (Oscar winner, 1946).

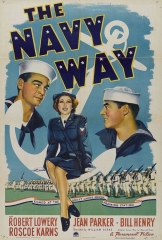

Newsreels and B-Movies

Some of the earliest, and quickest turnarounds, came in newsreels and b-movies. Newsreels were short fillers shown between double features, looking at the news of the week and other interesting events around the world. Newsreels encouraged women to enlist and showed the latest developments of the WAVES and SPARs, from the first officers to updates on uniforms, from boot camp at Hunter College to WAVES on the job.

B-movies, like The Navy Way, were meant to be shown on the undercard of a double feature. The films were made in just a few weeks and quickly released to theaters. The plots were often formulaic and the acting not as polished as in the main feature.

“The Navy Way”

The Navy Way (1944) was the first movie to feature WAVES. It tells the story of sailors in boot camp at Great Lakes. While at boot camp, the men meet the new breed of Navy personnel: the WAVES, as personified by Ellen, a pharmacist’s mate.

The film starred Robert Lowry and Jean Parker, and it was directed by William Burke, who was known as the “king of the b’s” for his ability to churn out low-budget films quickly and on time.

“Tars and Spars”

In 1946, the Allen Green-directed musical comedy Tars and SPARs was released. The film tells the story of a Coast Guard man stuck on shore duty, and the SPAR who thinks he was hero stranded in the ocean for 21 days with nothing to eat but gum.

The film starred Janet Blair and Alfred Drake, and featured Coast Guard veteran Sid Ceasar as the wise-cracking sidekick.

The Media Campaign

“Here Come the WAVES”

Here Come the WAVES was released on December 18, 1944. It tells the story of two twin sisters (a song and dance team when the movie starts) who enlist in the WAVES – serious Rosemary and scatterbrained Susie. Betty Hutton played both sisters. Bing Crosby and Sonny Tufts also star.

The Star Vehicle

The Navy was involved with The Navy Way, but to a much lesser degree than the feature film released later in 1944, Here Come the WAVES. The film starred Betty Hutton in a dual role, playing sisters Susan and Rosemary Alison, and love interests Bing Crosby and Sonny Tufts.

WAVE Public Relations officer Louise “Billye” Wilde was in Hollywood for much of the shooting of the film, to make sure that it met Navy standards. When the film put too much of an emphasis on the romance between Navy men and women, she encouraged director Mark Sandrich (not always successfully) to tone down the romance.

Girls on Film

Here Come the WAVES followed the Allison sisters from enlistment through being stationed at a base. Since it was a Hollywood film, the sisters were also tapped to star in a recruitment stage show, alongside a reluctant sailor who just wanted to go to sea, played by Crosby.

The film spotlighted the activities of real WAVES. Part of boot camp was shot on location at Hunter College with WAVES in training at the time acting as the extras. WAVE Dot Forbes Enes remembers marching for hours on end in her blue serge uniform one June day – singing one of the songs from the film over and over and over.

“Accentuate the Positive”

The film wasn’t just a way for the Navy to promote the WAVES on screen. It was a musical, so songs from Here Come the WAVES were heard on radio and sold to the public on albums and via sheet music.

Accentuate the Positive was the musical number that was the biggest hit from the film. It was nominated for an Academy Award as best original song in 1945.

In the film, Crosby performed the number as part of a blackface routine.