From “Gobettes” to WAVES (and SPARs)

Even before the United States entered World War II, the Navy was considering how women might be used to help win the war. The resulting negotiations to implement what to some was a controversial — and distasteful — proposal were both protracted and complicated.

From “Gobettes” to WAVES (and SPARs)

Laying the Groundwork

In the months before the U.S. became involved in World War II and immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor, behind-the-scenes discussions were underway if women should be allowed to enlist in positions other than nursing. For the Navy, a group of women from higher education would play an instrumental role in determining how women would be incorporated into service.

Unoffical Lobbying

Officially, there were no plans for women to be a part of any activities during World War II. But prior to the war, wrangling had been taking place inside and outside of the Navy. Joy Bright Hancock, the former WWI Yeomanette, was working as a civilian in the Bureau of Aeronautics. They realized the need for women, by her account in her oral history, but were frustrated by what they saw as a lack of vision by Naval officials.

Admiral Radford [the head of BuAer] wrote a letter to BuPers [Naval Bureau of Personnel] and asked what were their plans including women? You know what his answer was. “We have no plans, and we have no intention of using them.” And Capt. Radford said, ‘There we go again. No looking ahead by the black shoe boys.” Then began the struggle to get legislation introduced under the counter, which we did. And that put BuPers on the spot. They were really forced to take affirmative action.

BuPers had their own internal lobbyist for women in the Navy: Barnard College professor Elizabeth Reynard, who took a leave of absence from the college in early 1942 to take a special job as a civilian assistant to the Chief of Naval Personnel. But Reynard, unlike Hancock, had little history with the Navy, and it’s unclear if her efforts were successful.

Virginia Gildersleeve

Barnard College Dean Virginia Gildersleeve led a group of women in higher education who were quietly laying the groundwork with their students that women might be a part of any wartime effort.

Just a month after the Pearl Harbor attacks, Gildersleeve told her students and faculty her vision of the World War II world:

Are they really going to use women for “trained personnel”? Yes, they are. They have begun to realize that the “man power” of the country includes also the woman power, and that the government and industry will be forced to use women for nearly every kind of work except the front-line military and naval fighting.

Joy Bright Hancock

Joy Bright Hancock had a long history with the Navy. She served as a Yeomanette in New Jersey during World War I, eventually becoming involved with the fledgling Bureau of Aeronautics. Her first husband, Lieutenant Charles Grey, was among those killed in the crash of the airship ZR-2 in Germany. Four years later, her second husband died when the airship Shenandoah exploded over Ohio.

Hancock was largely responsible for public relations about Naval Aviation during the inter-war years. Her duties included editing the bureau’s newsletter, which eventually evolved into Naval Aviation News.

Elizabeth Reynard

Elizabeth Reynard was an English professor at Barnard College, and a close friend of Virginia Gildersleeve, before taking a temporary leave of absence to work at the Navy. Her job was to help figure how the Navy could incorporate women into the services. Other women in the military describe Reynard as artistic, creative and somewhat dramatic.

Reynard was born in Massachusetts, but moved to New York City with her mother after her father died, leaving the family virtually destitute. She was attending college at Barnard at the time, and worked as a copywriter while attending school. After graduation, she was invited to teach part-time at Barnard.

After helping to set up the WAVES, she would later be transferred back to New York, where she was credited with the creative and highly successful training regimen which WAVES would use at Hunter College.

From “Gobettes” to WAVES (and SPARs)

The Proper Role

The successful integration of the Yeomanettes into the military in World War I served as a template when the Navy looked to ease a similar personnel crisis during World War II. But Congress, and other leaders, worried about the proper role for women in the military.

Women’s Advisory Council

Reynard, having little success inside the Navy, began to reach for help from the outside. With the assistance of Gildersleeve, she organized the Advisory Education Council. The group was made up of women from around the country, drawn mostly from academia, including Meta Glass (Sweetbriar College/American Association of University Women), Ada Comstock (Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University), Emma Barton Brewster Gates (wife of University of Pennsylvania president Thomas Gates), Dean Harriet Wiseman Elliott (University of North Carolina, later replaced by Alice Baldwin of Duke University), Alice Lloyd (University of Michigan), and Ethel Gladys Graham (wife of UCLA political science professor Malbone Graham).

The Council was unofficially charged with giving advice about and helping promote the idea of women in the Navy. It acted as a liaison of sorts between the Navy and the community. Its existence linked the Navy, in the minds of the public at least, with collegiate education, i.e. respectability. The Council was a powerful public relations tool, reassuring the public that the Navy was a “safe” place for women in the military.

WAAC

As the Navy’s negotiations were ongoing, the Army jumped to the forefront, pushing Congress to approve the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC). The bill was first introduced in October of 1941, and was passed by Congress in May of the following year. Not everyone accepted the idea of women in the Army.

As Leisa Meyer notes:

The public debate during World War II focused on concerns that the creation of a corps of “female soldiers” would lead women to abdicate their responsibilities within the home and usurp the male duty of protecting and defending home and country.

The women weren’t given full status in the Army, but instead were only an auxiliary to the “regular” male corps.

Will They or Won’t They?

Those in the Navy who supported a woman’s corps pushed to avoid the divide that separated the WAAC from the regular Army. They thought the women should be fully “in” the Navy, subject to Naval regulations and command rather than an external auxiliary like the WAAC. But others, including many members of Congress and the Navy’s Chief of the Bureau of Navigation Chester Nimitz (who would later lead the Pacific fleet), found the idea of women in the military in positions other than nursing to be unacceptable.

However, by the time Japanese fighters attacked Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, the increased need for forces to fight a war on two fronts made it clear even to detractors like Nimitz that the Navy would need to accept women in uniform. As Jean Ebbert and Mary-Beth Hall point out, Secretary of Navy Frank Knox recommended establishing a women’s:

reserve as a branch of the Naval Reserve, appointments and enlistments … would be made only in time of war and were to expire no later than six months after the war’s end.

This opened another round of bitter wrangling within the Navy and the Senate. At issue was the women’s fully integrated status within the Navy; objectors wanted women to be an auxiliary, like the WAAC. Nonetheless, the Navy began proceeding on the assumption that women would soon begin work. The Women’s Advisory Council, headed by Barnard College Dean Virginia Gildersleeve, began lobbying members of Congress (and President Roosevelt via his wife Eleanor) about the women’s reserve, emphasizing the security and discipline the women would have. Finally, Navy and Congressional detractors relented. President Roosevelt signed the bill establishing the Naval Women’s Reserve into law on July 30, 1942.

From “Gobettes” to WAVES (and SPARs)

In the Navy

President Roosevelt signed the bill establishing the Naval Women’s Reserve into law on July 30, 1942. The women became known as WAVES, short for “Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service.

The WAVES Emerge

Even with the roadblocks in Congress, it was also apparent that the Navy – like civilian industries before it – needed more than just men to serve at sea and at home. Civilian factory women were known as “Rosie the Riveter”– the Navy needed an equally snappy name. This was something Elizabeth Reynard, who had struggled with the more conservative nature of the Navy, could do. It offered a use for her creative talents. Mildred McAffee recalled:

(She) played with two letter and the idea of the sea and finally came up with ‘Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service’- W.A.V.E.S

Emergency, she thought would comfort admirals and others on the fence about women’s participation – implying it was only short term. The new name was an immediate hit with both the Navy and the press – and the would-be enlistees found it fairly snappy too. It was also a far more acceptable nickname to others being bandied about in the press like “gobettes” or “sailorettes.”

Mildred McAfee

The Navy had decided that it was going to have somebody at the head of this organization who was not politically related or known. They had decided to try to get a college president on the principle that the Navy knew enough about the Navy, but they didn’t know much about girls, and that somebody who had been working with young women would be the kind of person they’d look for.

– Mildred McAfee, World War II Navy WAVE Commander

Mildred McAfee was just thirty eight years old when she was tapped to lead the WAVES. She also fit an image desired by the Navy: single, daughter of a pastor and dean of a women’s college, Wellesley. She came on the recommendation of Virginia Gildersleeve and the Navy’s advisory council. Joy Hancock said she gave the WAVES a jolt of class.

Prestige…she brought that to us. I don’t know anyone else who could have done it as well

said Hancock in her oral history.

The First Officers

The initial group of officers was invited to join the WAVES; it included future WAVES leader Winnifred Quick Collins as well as future SPARs head Dorothy Stratton. These recruits were rushed through a pared down version of officer training and graduated in late September 1942 before official recruitment began.

Women involved in the organization of WAVES, such as Mildred McAfee, Elizabeth Reynard, and Joy Hancock, avoided training altogether.

Navy Recruitment

Recruitment stations were set up around the country, to gather recruits for both the officer and enlisted ranks.

When the Army first opened its doors to women, lines snaked around the block outside of recruiting offices. The lines were often filled with women who had no intention of actually serving, but who just went down on a lark. As a result, there was a lot of unfavorable publicity in newspapers about the type of women “enlisting” – most of whom never actually enlisted.

By contrast, the Navy initially required that interested women write a letter of intent to their local procurement office. The letter would be reviewed by a recruitment officer, and if all seemed well the woman would be sent an application plus a specific appointment time for an interview. While the Navy and Coast Guard later loosened this recruitment protocol, initially the Navy was in complete control of the image of even potential recruits.

The Navy also made sure that recruitment offices were set up in locations that conveyed class and sophistication. Rather than downtown or in shoddy neighborhoos, the Navy recruited women in more “uptown” surroundings with officers and enlisted women reporting to the same building. This was in contrast to the WAAC, which intially had women report to the same offices as men, often in sketchy locations. “I was very happy about that because I thought that set a tone of it being in a nice neighborhood, shall we say,” McAfee recalled. Even the location of the recruiting office conveyed the message the Navy was somehow “better” than other branches of service.

From “Gobettes” to WAVES (and SPARs)

Other Women’s Corps

Other military branches were similarly considering how women could be involved during war times, and looked to the success of the Navy for a template for full integration.

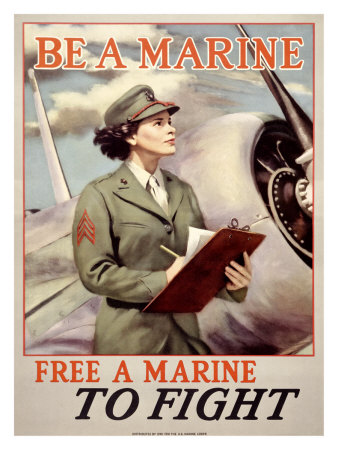

Women Marines

The likely-fictional Lucy Brewer is often credited as the first woman to serve in the U.S. Marine Corps. As legend goes, she snuck in – during the War of 1812. Sanctioned enlistment came during World War I, via the same loophole that allowed for Navy Yeomanettes.

The Marine Corps Women’s Reserve was founded on February 13, 1943. Approximately 19,000 women served in all, under the command of Col. Ruth Streeter. Because most of the male Marines were in the Pacific battling the Japanese during the last year of the war, more than half of all stateside positions were held by women.

Ending the Auxiliary

On August 9, 1943, the WAAC was replaced by the WAC (Women’s Army Corps), a reserve force, which like the WAVES, was fully integrated into the Army. In all, more than 350,000 women served in World War II, including 140,000 WACs, 23,000 Women Marines and 1,800 WASP. Seventy-six thousand women served as military nurses.

The WASP

In 1939, the U.S. established the Civilian Pilot’s Training Program. The idea was to train at least one woman for every ten men, but two years later the U.S. banned women from participating in the program.

But despite the government discouragement, women were still flying planes. In September of 1942, two small groups of women were allowed to begin ferrying military planes across the U.S.: the Women’s Auxiliary Flying Squadron and the Women’s Flying Training Detachment. A year later, the two groups would merge, creating the WASP (Women Airforce Service Pilots).

Unlike the other branches, the WASP remained a quasi-military organization and never received full military status during the war years.

From “Gobettes” to WAVES (and SPARs)

Coast Guard Recruits

The Coast Guard falls under Naval administrative jurisdiction during wartime. So during World War II, when the Coast Guard decided to recruit women for its reserve services, it followed Naval standards.

First WORCOGS, then SPARs

The women’s reserve of the U.S. Coast Guard was established, on November 23, 1942. Former WAVE officer Dorothy Stratton was named as SPAR Director. Like McAfee, she helped the SPARs avoid an unwieldy nickname. The Coast Guard initially proposed naming the new branch the Women’s Reserve of the Coast Guard, or WORCOGs for short.

Stratton suggested a name which played off of the Coast Guard motto: Semper Paratus, Always Ready. The SPARs were born. In a memo to Coast Guard Commandant, Vice Admiral Russell Waesche, she said:

The initials of [the Coast Guard’s motto] are, of course, SPAR. Why not call the members of the Women’s Reserve SPARs?. . . .As I understand it, a spar is. . .a supporting beam and that is what we hope each member of the Women’s Reserve will be.

Dorothy Stratton

Stratton transferred to the Coast Guard on November 24, 1942 and was not only its first leader but also its first woman accepted for service. She was promoted to the rank of Lt. Commander

SPARs Jurisdiction

While the SPARs fell under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Navy, they for the most part trained in separate facilities (the Coast Guard set up their own boot camps). This was typical of military protocol. Male Coast Guard members were also under Naval jurisdiction during wartime.

Why the Coast Guard

I had a couple of aunts that went in. I had one aunt that was an Army WAC and one that was an Army nurse. And so, I was aware. My grandma had two girls and three boys in it, the military. You know she had the stars in the window, always hoping it wouldn’t turn gold … Seeing all the Navy people and some Coast Guard people at the base where I worked, I think that had a lot of influence. I didn’t want to go into the Navy because they could send me right back into my old job. I wanted to see some country. (laughs). I wanted to see something besides Utah. (laughs) I was debating between the two and that really sealed it.

– Jane Ashcraft Fisher, World War II Coast Guard SPAR

.